Although I’m an actor, this is my first Edinburgh fringe. I had always avoided it, imagining an avant-garde scene where unitarded performers dragged themselves yearly to throw all their money into a pit, in the rain. I couldn’t be more wrong: for the 24 hours I spend here, it’s actually quite sunny.

It is definitely a place legends cling to. In 1987, Mark Ravenhill put on a “play” here called Seven Hours of Sleep, which ran from midnight until 8am, because his company couldn’t afford accommodation. (It wasn’t a free event.) Friends relate stories of misguided, nudity-soaked productions; the interpretive-dance story of Jimi Hendrix, featuring shonky, unlicensed covers and a comically large wang. These are the droids I’m looking for.

The plane to Edinburgh is quiet. Most acts will take the train, or Megabus, or horse and cart. On arrival, I immediately find a friend. Sophie Woolley is a very funny actor-writer, on a pilgrimage. In her 20s, hereditary deafness ruined her ability to enjoy the festival that inspired her to get on stage. She performed her own show When to Run here in 2006, but “didn’t watch anything else, because I couldn’t hear. I wasn’t able to be spontaneous, which is what festivals are for.” Then two years ago, almost totally deaf, she had an operation fitting her with a cochlear implant; it restored her hearing on one side. Twenty years since she first came, she has returned to recapture the thrill of being a punter.

She lets me tag along until I find my feet. (I feel safe with her. Her implant is by a company called Advanced Bionics and she is staying in a Japanese-style capsule hotel, so as far as I’m concerned, she is from the future.) We check out the Free Meditation Class, a one-man event above a pub, which sounds like a relaxing way to ease me in.

“After an hour, I’m going to pretend to burn myself to death,” announces an intense young man. We’ve misread the tone of the show, which recounts the violent act of a self-immolating Buddhist monk (but not the one everyone knows). It is an unsettling monologue, switching between first and third person, interspersed with a history of the banjo. I don’t really know what’s going on. There are hundreds of curios like this – staged for free, free to attend, the fringe of the fringe. Consensus will gather – people are already passing round Scotsman reviews, word-of-mouth buzz, Phill Jupitus’s hot tips – but the first days of the festival are a smörgåsbord of gammon, spanners, caviar and turds, approached blindfolded.

Sophie and I split up. She’s off to see Aidan Killian, a standup with a show about the holy trinity of whistleblowers: Assange, Manning and Snowden. (“Could be brilliant, could be bollocks. Perfect!” she says.) I head over to Bruce, a puppet show starring a crudely cut block of yellow foam. Puppetry really is an incredible form. How do they force you to invest your most human feelings into an avatar that looks as if someone stuck eyes on a cheddar and broke it in half? At the end of the show, I’m wet-eyed and useless.

I spend the afternoon profoundly lost, running between theatres, collapsing into back rows and sweating like a pig on a date. As the festival has grown, venues have expanded into platforms, becoming geographical jokes in the process. Whenthe Assembly Rooms outgrew the actual Assembly Rooms, they shortened their name to Assembly and moved to various locations, including Assembly Hall, the former home of the Scottish Parliament. In the meantime, another group took charge of their original building and name, prompting a headspinning legal dispute. “If they can fit three stools and a desk lamp in a room, they’ll call it a venue,” I’m told by Hannah and Kim, graduates of Edinburgh University who fell in love with the festival and return each year to volunteer. “I was at the Hot Dub Time Machine disco the other night, thinking: ‘Why does this place look so familiar? Oh, I graduated here.’”

Speaking of which, theatrical rehashings of celluloid smashes are in. There is aJurassic Park show, and a one-man Breaking Bad. I check out Thrones! The Musical, despite never having seen the original Game of Thrones on TV. (I know, I know, shut up.) Weirdly, most of the jokes go over my head.

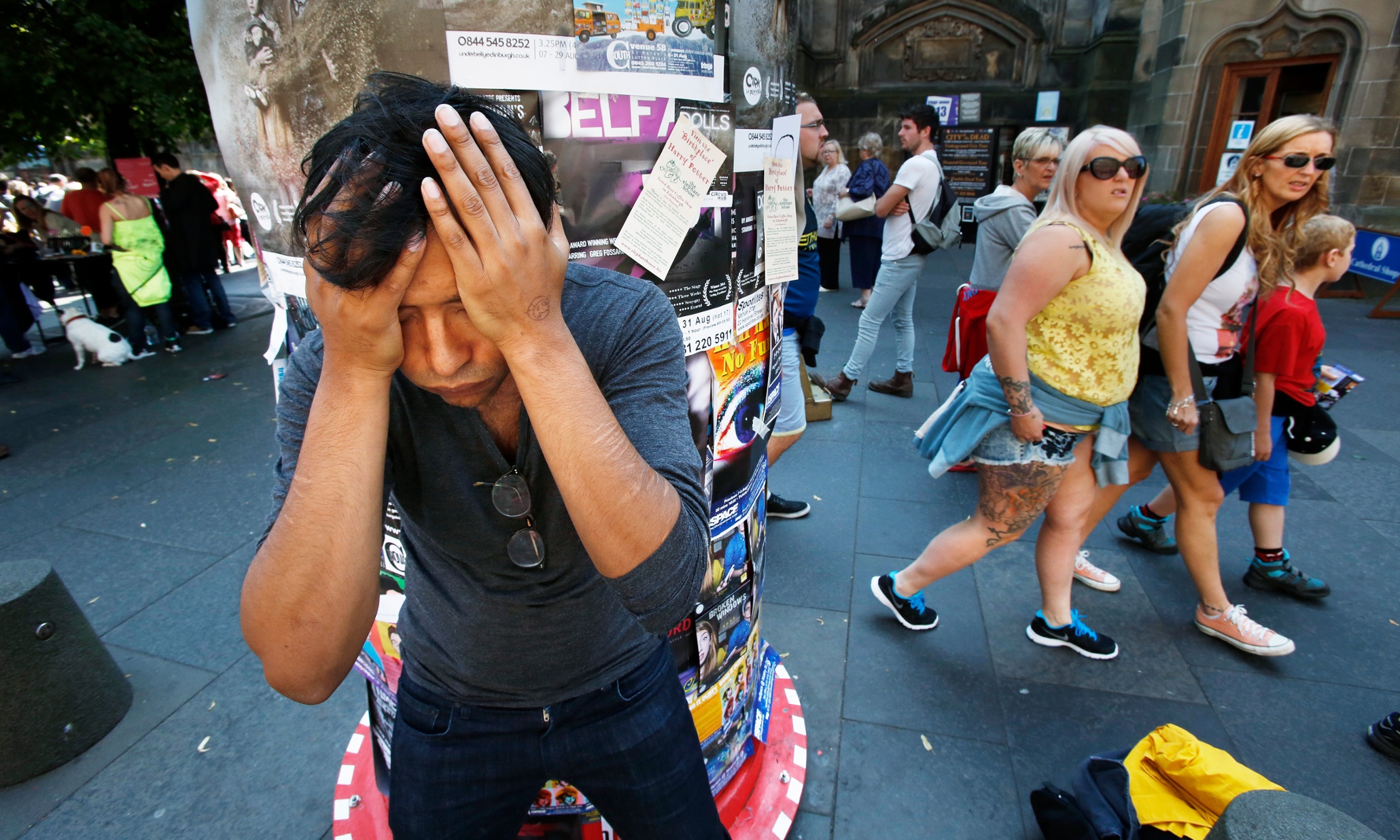

Then I sit on the kerb and eat some mixed nuts. Mixed nuts is a pretty good way to describe Edinburgh in August. Troupes in blue spandex earnestly debrief each other on corners. Two girls in sherbet wigs called Flossy and Boo make me tweet a selfie with them, just because Phill Jupitus did earlier. “This is what you’re looking for!” promises a man, handing me a flyer that reads “Scottish Falsetto Sock Puppet Theatre”.

I meet up with Sophie again. She’s on a high, having seen and loved Chicken, an Orwellian dystopia, followed by experimental flute and electronic loops, courtesy of Glasgow musician Shona Brown. Her eyes are ablaze with art and its nearly infinite possibilities. She asks what I’ve been up to. “Thrones! The Musical,” I say. “I’ve not seen the TV show,” I add, limply.

What shall we see next? Sophie eyes a flyer for the show Charolais, which has a large picture of a cow on it. “After Chicken, I’m quite into farm noir,” she hints. But we don’t make it. We’re accosted by semi-naked beautiful people, one of whom has hairy legs and horns. Inviting us to Follow the Faun, they take us into a dark room with eight nervous strangers. For the next 45 minutes, this demonic, sexually explicit faun-man leads us on a shamanic journey of ritual choreography. Banging music and trance visuals swirl, as we sprout our own horns, ride unicorns and fellate the universe. I’ve not dressed for a psycho-spiritual odyssey, and am once again soaked in sweat. It’s strangely liberating.

Sophie has to catch a train home, assuring me it is not because I’ve just made her attend a pagan transubstantiation raverobics class. It’s late evening. Every night, a firework display shrouds the castle’s ramparts in smoke, like the aftermath of battle. Drinkers throng the streets, singing Amy Winehouse and Adele. And the shows take a turn for the lewd.

At Dark Side of the Mime, a man in pancake makeup and a beret mimics exaggerated sexual acts on my embarrassed body. He is Finland’s actor of the year, apparently, and confirms everything I suspected about mimes. At Spank!, the long-running frat-house of party comedy, I leave the instant they tell us one audience member will be asked to get naked. I don’t like those odds. The “Edinburgh institution” Late’n’Live is a comedy bearpit in which the comedians are drunker than the audience, and heckling is encouraged. A large-thighed man next to me keeps bellowing “I think she works in McDonald’s!” every few minutes, without any context whatsoever. I feel untethered from reality.

I find a bar instead, and start drinking to catch up with the entire city. There are performers everywhere, doing the same. A sticker on the wall reads “Edinburgh or Bust!”, as if the two things were mutually exclusive. “I’ve put 10k into this,” Larry Dean tells me. He is Scotland’s 2013 comic of the year, and funny even when detailing financial anxieties. Surely it’s a hell of a gamble?

“Not everyone is waiting for their ‘big break’”, explains James Farr, comedy aficionado. “You’ll see acts here who aren’t necessarily TV-friendly, but are brilliant live performers. People such as Kate Smurthwaite, Don Biswas, Ivor Dembina – it’s a community. Phill Jupitus still comes back to play free shows.”

I stumble into the early light, pigeons clearing the debris of the night. Edinburgh is a city of old stone, basking like a reptile getting its blood up. In a few hours, everything starts again. In former veterinary school Summerhall, I watch Some People Talk About Violence, a faux-verbatim show about an unexplained act of brutality, staged at breakfast. Actors kneel on the floor facing each other, stuffing crackers into their mouths. “Every day I scream into my jumper because I’m so alone,” says one.

I don’t really know what’s going on. But I’m hardly Kenneth Tynan; I’m hungry, knackered and tired of people telling me about Phill Jupitus. My 24 hours are up and, despite myself, I’ve completely loved them. It is a baffling, hilarious carnival of pure creativity. I remember James’s slurred yet rousing words. “There’s magic in those little rooms. If you’re a performer, playing to two or 200 people, understand this – you’ve arrived.”

[“source-theguardian”]