Transitioning from male to female was empowering—but the harassment that followed taught me new things about power and womanhood.

Passing is a complex and controversial topic. Typically, when people talk of passing—a shorthand for “racial passing”—they are referring to African Americans presenting as white in order to escape slavery or discrimination. However, in recent years, more confounding types of passing have made headlines. The most infamous is probably the case of Rachel Dolezal, a white woman who passed as black, and comedian Mindy Kaling’s brother, an Indian American man who posed as black to get into med school.

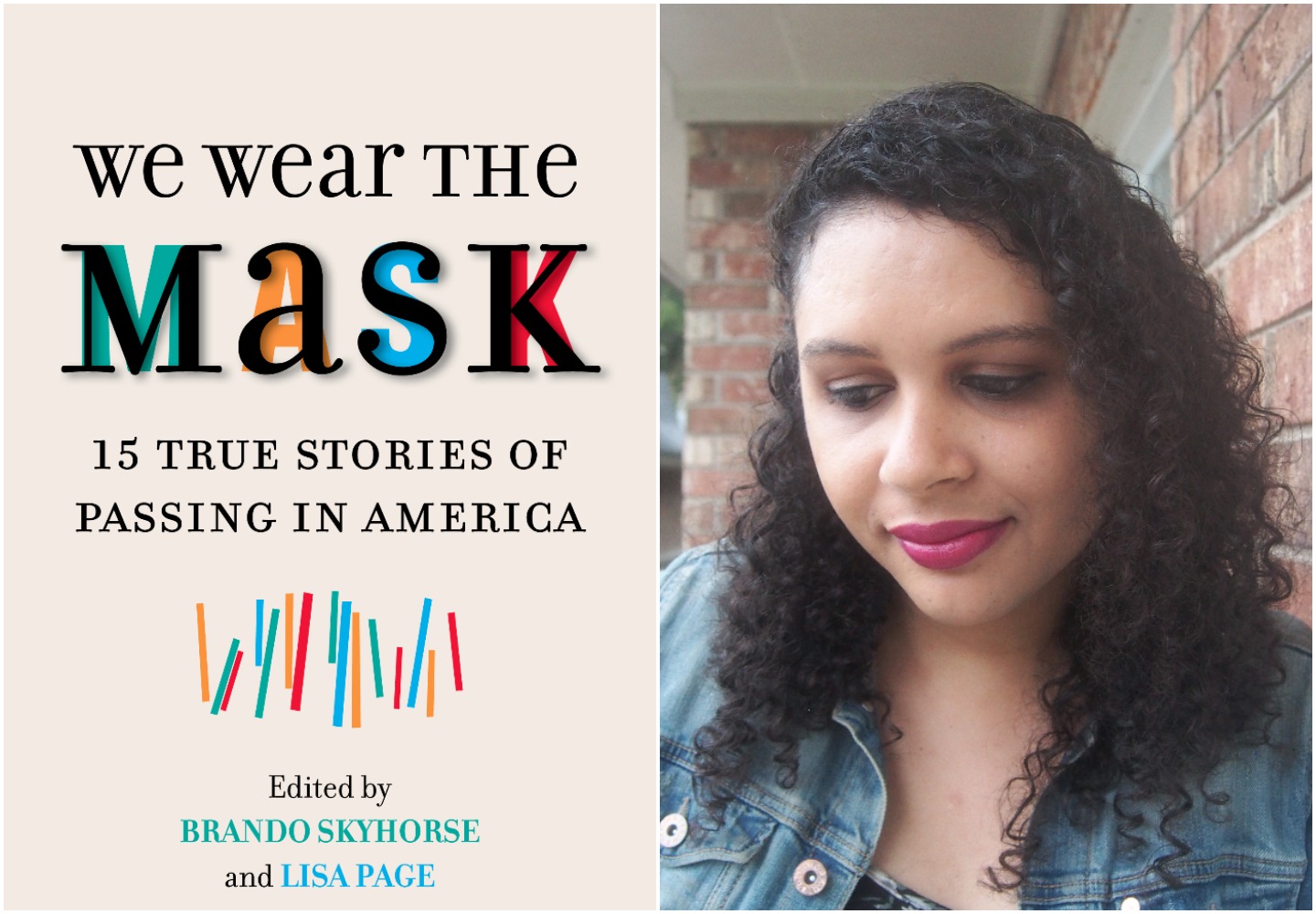

We Wear the Mask: 15 True Stories of Passing in America is a forthcoming anthology edited by Brando Skyhorse and Lisa Page that explores the numerous reasons why and how some people pass: “opportunity, access, safety, adventure, agency, fear, trauma, shame.” Skyhorse, a Mexican American writer who passed as an American Indian for 25 years, and Page, a biracial woman whose black grandmother passed for white in order to go to college, have gathered an impressively diverse set of new essays on passing that span race, background, class, orientation, and nationality.

In the excerpt below, Gabrielle Bellot writes of her experience as a trans woman of color passing as a cis woman and the validation—and fear—that followed.

—James Yeh, culture editor

The Beauty and Terror of Passing as a Woman

The first time a stranger propositioned me as a woman was in a room full of sculptures in a museum. He was a security guard at the National Gallery, far larger and taller than I was, and had waited for the other tourists to leave the room before he began talking to me. At the time, fewer than a handful of people knew I was transgender, and I had traveled to Washington, DC, a place I had never been and had no family in, presenting as a woman. All of my IDs still had an M for my sex and an old name that could not have been a woman’s, and my voice was still too filled with a deep rumble for anyone not to see I was trans after a few words.

It was the week of Thanksgiving. Snow had begun to fall. I had walked to the museum in the long black dress, flowing brown coat, and merlot lipstick of a lonely romantic, and although I knew I could already pass as a cisgender woman visually now if I wore makeup, months before I would begin taking hormones, I had not actually thought that going to the museum would be any different from how it had been in the past as a male. The streets and subway ride from the carnival atmosphere of Union Station had seemed a bit unnerving, but the city seemed relatively empty, and until the guard spoke to me things hadn’t really seemed that different.

The guard had seen me eating in the museum café from a distance, but it was only when I ended up in a room of sculptures with the guard again that I truly felt the terror of passing as a trans woman for the first time. He asked me if I was getting “nice” photos with my camera and if I had had a “nice” lunch, smiling widely as he inched closer with each question. Instinctively I did something I would regret for many months of harassment later: Rather than ignoring him, I smiled back. Finally the guard asked where I was from. I mumbled, “Caribbean.” He nodded, saying, “Yes, yes,” and that I was beautiful. Then he grinned and told me to call him soon to have sex with him.

I was so scared that I lost my language. “Maybe,” I said, afraid a firm no might get him angry. Then I hurried to the second floor. I must have looked like a shipwreck victim, eyes wide and flitting. Here was a man who was supposed to protect me trying to force himself upon me, a narrative I had seen in so many lurid cases of police officers abusing their authority.

Watch on Broadly: Meet Trans Civil Rights Hero Gavin Grimm—and the Pastor Who Calls Him a Girl:

I began looking at every male guard, listening to their footsteps. I began learning, without looking, when I was alone in a room, when to move on rather than stay by myself. I had begun to learn what it is like for so many women, trans or cis, to simply be in space, to be aware of where your body is and who is looking at it and who is considering following it.

The incident with the guard had been short and quick. Later, I wondered if perhaps the guard did not even realize his position of power or how the fact that he had waited until we were alone to speak to me like this might frighten a woman on her own. In the end, I left the museum early, glancing back as I walked through the light snow, hoping I would not see the guard walking after me or hear his footfalls behind me. The security guard had betrayed me, just as police officers have too often betrayed young black American men, by removing the illusion that he was just there to protect.

When I finally came out as a queer transgender woman at 27 in Tallahassee, Florida, where I was doing my graduate degree, it saved me from committing suicide.

It started happening almost every day. With a guard at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, who made me take a photo of him on his own phone, in order to ask me out. With a guard in the Peacock Room of the Freer Gallery. It happened with man after man on the streets. It happened with an old Russian taxi driver, who kept telling me not to leave his cab because he wanted me. Another man had walked me to the Russian’s cab, telling the driver, who he must have known, “I have brought you a beautiful girl.” I was an object, an objective, and, if they found out I was trans, often objectionable. It became common for men I did not know to speak down to me, often so subtly that I doubted they were aware of doing it. What had seemed so large at first now had become a new norm, this harassment for being seen as a woman: sometimes comical, sometimes annoying, always a bit unnerving, sometimes terrifying.

Yet I still worried each time a man catcalled or propositioned me that I might face violence if he realized I was trans. After all, it is not uncommon for trans women to be assaulted or even killed by someone who reacts in fury to finding out the woman he was flirting with is not cisgender. Once, I looked up at the night sky on my way back from the metro and a thought flitted through me: This is like living on a new planet. My female friends had told me stories of being catcalled and stalked before, but I had never understood them until now.

Passing, suddenly, was always a step behind me.

For Seneca, it is possible to turn off noise outside if you can silence it inside yourself. “There can be absolute bedlam without,” he wrote in “On Noise,” “so long as there is no commotion within.” Living as a trans woman, that has become my mantra: to live without screams, inside or outside, so I can keep smiling, hoping, dreaming.

When I finally came out as a queer transgender woman at 27 in Tallahassee, Florida, where I was doing my graduate degree, it saved me from committing suicide. It saved me—even as it meant losing something else. I had already decided, months before, that I would not return to Dominica until I could feel safe there as an openly transgender woman. Luckily, I was a dual citizen; all the same, Dominica was my home, and now I had lost it. My parents themselves told me not to return. I cried, many nights, at the things my mother said to me, things I knew mothers could say but never imagined mine would: that I would be disowned, that I should forget I had a mother, that I was a failure and an abomination against God, that she herself now felt suicidal.

I still hear those words, sometimes, when the night is too quiet.

I prefer to think of identity in terms of fields of stars, constellations. For me, it is easy to call one field of stars Woman and another Man, and then, from there, to see how my identity forms a constellation within the field of Woman, even as I have lived before in a different configuration of stars. For some of us, jumping between the fields is simply the norm. Some constellations branch between these two main fields, and others, off in a nearby inky elsewhere, do not really fit within either. There are many constellations in the star fields of Man and Woman; to be a transgender woman is to make up one of the configurations of womanhood, just as tall women and tiny women and women born without uteruses make up their own, even as what my configuration looks like may differ, in its own way, from what another trans woman’s looks like, and vice versa. We will not, contrary to certain cis women’s fears, erupt into supernovas and destroy the whole field, or turn into black holes and suck everyone into our space. We are women.

I know this, internally, intellectually. But it’s easy to forget where you belong in the star fields when you are confronted, day after day, with the fear that you may not pass as a cisgender woman when you enter this restroom or walk down this city block or put on this cut of bathing suit, and you begin to wonder, as you’ve wondered so often before, if your position in that constellation is precarious.

It can be difficult, though necessary, to learn that passing is not our goal if we identify as binary transgender women, as I do. We are women, no matter what we look like, even if not all of us can pass for a woman by the statistical norms of what cisgender females look like. There is nothing inherently wrong with wishing to pass visually, aurally, or otherwise as cisgender; but we do ourselves an intellectual disservice if we fail to realize that the language of passing implies both temporariness and trickery, and aiming to be recognized as women, regardless of what we look like, is a much greater goal.

It can be a sudden shock, as Virginia Woolf described in Moments of Being, to realize that you have accepted yourself as you. That you have come to love yourself. That you have come to learn you would let yourself into your own home if you opened your door at a knock, and found yourself standing before you, a woman without reservations. If I can recognize myself as a woman—well, that’s a start to feeling more at home in the field I belong in, to feeling more at home in my language.

Perhaps this is what it means to be a binary trans person: to hear someone say “woman” or “man” and not feel isolated by their words, or even by your own.

And yet, sometimes, passing makes me feel validated. Sometimes I smile after a man on the sidewalk catcalls me crudely, not because I like being catcalled but simply because I know someone saw me as an attractive woman. Sometimes the fact that men on online dating sites are shocked that I am trans when I tell them—invariably, they miss it in plain sight on my profile—makes me feel happy. Passing, like prettiness, is a privilege; passing, like prettiness, can also be a peril, if someone believes we are deceiving them.

I remember how I thought of passing the first time I let a man fuck me. How I thought of passing, even though he knew I was trans, had contacted me, indeed, because he wanted an experience with a trans woman. I remember the conflicts: how I wanted to be fucked so badly, yet feared the very thing he wanted from me. How, even though I had invited him into my home, I felt the need to look as feminine as possible when he opened the door, out of the foolish fear that he would flee. And how I felt so happy, finally, when I realized that he wanted me simply for me, not for a version of me that passed, how I felt like a queen stretched out on my bed with him atop me, a queen who was being treated like royalty by this gentle giant of a man, regardless of what genitalia she did or didn’t have. I remember, then, how the noise left my head, and all I felt was joy. Yet even now, so long later, each time I sleep with someone else, man or woman, cis or trans, I think again of whether my body passes.

Sometimes I smile after a man on the sidewalk catcalls me crudely, not because I like being catcalled but simply because I know someone saw me as an attractive woman.

I thought of passing too on the night burglars broke into my apartment, tearing through it like a brief tornado, strewing my clothes and student papers and drawers all over the floor. I thought of passing in the terror of opening doors and turning on lights and hoping no one was lying in wait, for I knew that if they thought me a cis woman, they might try to rape me, and if they found out I was not one because I had passed too well on the trips from my home they had perhaps been monitoring from the shadows or if I had not passed and they knew all along I was trans, well, if they knew either way, they might still rape me, but they might also beat the shit out of me not simply for being a woman, but for not being the kind of woman they could believe in, respect enough, if such an absurd term can apply in such a situation, to violate and leave behind without a fractured skull. It can happen to you as a cis woman or a trans woman, this violence, yet as a trans woman who can pass, the specter of punitive violence so often looms larger. I thought of passing when a police officer came to my home and I tried not to let my voice dip down too low, out of fear that he might, as some officers have told trans women in the past, tell me my being so open with such a “lifestyle” had brought this upon me, had made me too visible a target just for being myself.

I was still, even then as the victim of a crime, looking for the language of passing.

The first time my mother referred to me as her daughter was at a concert in Tallahassee. We were sitting at the back of the Ruby Diamond auditorium in the intermission, and the couple in front us had stood up to stretch their legs. My father struck up a conversation with the man about the brilliance of the cellos. In a moment, we were all speaking to each other. After a while, the man introduced himself and his wife. I hesitated.

I had come out to them two years before. I had seen them in person a few times since, but only outside of Dominica. This time, they had come up for medical appointments, as they could find better treatments in the United States than in our island.

I was in a blue dress. They had become accustomed to seeing me like this. My father had come around first, offering his support to my transition, but he still struggled with using my new name and pronouns because the old ones were rooted so deep in his memories. My mother, I knew, loved me, yet my transition still hurt her. Even as she sat next to me, she seemed far away, as if her body was here but her mind was elsewhere.

“And this is my daughter, Gabrielle.”

I almost began to cry. Acceptance does not mean all is well—I still can’t return home without putting myself or my parents in potential danger. And my mother would still tell me, after this, that she wanted her son back, that I needed to return to God and maleness alike, that I was not her daughter despite such situational slip-ups, that I was setting myself up for a life of misery because, to her, queerness was the same as incomprehensibility, as failure, as stepping on a burning star with arms outstretched. I learned to dread calling my parents simply out of the fear that my new voice—the one I’d trained to have a new resonance and pitch, as hormone therapy for trans women has no effect on our voices if we begin transition after puberty—would sadden them more, as my mother had told me one day, on the verge of tears, that I no longer looked or sounded like the child she had raised. Acceptance, like rejection, is rarely absolute. But we grow as we learn more. We become bigger as our capacity for love does, even if our steps are small.

On most days, I just want to be able to point to my constellation and think, Yes, that’s me, without hearing any footfalls, any noise, nothing but me and the marvelous mundane calm of recognizing myself for me.

Perhaps recognition and love share the same mirror.

Follow Gabrielle Bellot on Twitter.

Adapted from Gabrielle Bellot’s essay “Stepping on a Star,” from the forthcoming collection, We Wear the Mask: 15 Stories about Passing in America, edited by Brando Skyhorse and Lisa Page (October 2017, Beacon Press). Arranged with permission from Beacon Press.

[“Source-ndtv”]