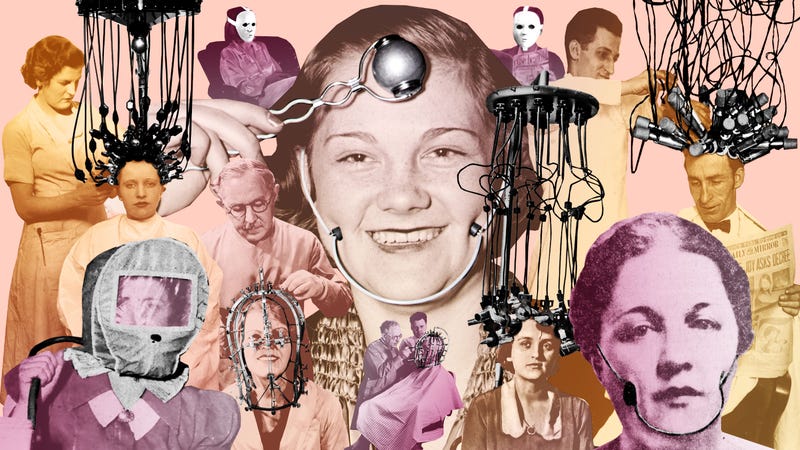

You are ugly, and if you didn’t notice, perusing a history of American cosmetic marketing will point out all of your innumerable flaws until you feel that god has damned you. It tells you your genetic traits are unsexy and then makes you pay for it. It denies science. It racially segregates. It sexually fetishizes physical characteristics of children. It espouses self-inflicted pain and adds scalpels to the handbag of normal self-maintenance tools. It burns, it stings, it pricks, it irritates, and it occasionally causes cancer. It is beauty.

But even within those very broad confines, product inventors occasionally overstep. Here is a brief review of some of those beautifying gadgets, which, if not for torturous pain, quackery, government interference, surveillance technology, or Clockwork Orange–esque stylings, might still be darkening our bedside tables today.

The permanent wave machine (1906)

The typical beauty salesperson first informs you of what’s wrong with you and then tells you what you need to buy in order to change that. In the early 20th century, your problem was straight hair; your fix was sitting motionless for roughly ten hours under 60 pounds of scalding brass irons hanging half an inch from your scalp.

“Nestle’s Improved Permanent Hair Wave means the imparting to the straightest and lankest hair & wave, which in texture, character, desirability, and appearance cannot be distinguished from the natural grown wavy hair,” reads a newspaper adfrom 1908, listing a perm for £5–$760 in today’s dollars. First, the hair was treated with sodium hydroxide (a lye used today in relaxers and Drano to dissolve, among other things, hair), making it softer (or weaker) then heated with two-pound brass rollers, which were suspended with a set of counter-weights to avoid searing the client (with mixed results). The ad went on to assure that the process was “absolutely non-injurious,” which it was not; various accounts state that inventor Charles Nestle (née Karl Nessler) burned his to-be wife’s Katharina’s hair completely off twice before debuting the machine in London in 1906.

In a 1971 interview with Pennsylvania’s The Morning Call, Nestle Company representatives mention that the initial procedure was “12 to 20 hours of misery for both the operator and operatee”–both scorched–and the device was nicknamed “The Fiery Dragon,” and that during the adaptation phase to electric power, the “ceiling collapsed” on a few unfortunate souls who may or may not have survived [unclear]. “At first, women were scared of the new process and only very brave women of great wealth decided to take the risk,” the reps told the paper. “Almost all of them got burned slightly.”

The madness of crowds finally swept up middle-class women and under the cranial frying pan when Nestle managed to demonstrate publicly that he could perm a volunteer without seriously injuring her. In 1915, he opened a wildly successful salon chain across America and tweaked the device with safer affordable versions, albeit with the occasional burn victim, and by 1928 he said to have had amassed a $3 million fortune ($44 million today).

Nessler lost all of his money in the Wall Street Crash of 1929, but history gives him credit for advancing technology and even enriching women’s lives. LIFE Magazine’s 1951 obituary “A Revolutionist Dies” claims that Nessler single-handedly gifted women with the communal culture of the beauty salon. Whether or not you personally feel perms are a net benefit to society—and if so, conclude that the perm as a hair option is worth the possible human sacrifices made—Nessler’s initial fail led to the eventual success of the perm.

The dimple-maker (1930s)

Mrs. E. Isabella Gilbert’s Dimple-Maker (aka the “Dimple Digger”) played on America’s desperate yearning for dimples, debuting in 1936, the same year when Shirley Temple’s dimples speckled the nation in posters for her new movie Dimples. “Any person feeling that the absence of dimples from his cheeks is a slight by Nature, easily can supply the deficiency,” stated an October 1936 piece from Pennsylvania’s Republican and Herald.

The desire was so intense that within a decade, door-to-door dimple-maker peddlers had bilked housewives from coast to coast. A 1946 San Francisco Examiner piecetitled “Swindler’s Harvest: Danger at the Doorbell” reported that “[i]n one community alone, a squad of salesmen took in $8,000 [over $100,000 today] before they were chased out.” Whether or not that’s true, Weird Universe’s Alex Boese hunted down the contraption’s fate: a 1947 national exhibition of quack devices assembled by the American Medical Association, which even cited doctors’ claims that the dimple-maker may cause cancer.

Beauty micrometer (1932)

The concept of the “beauty micrometer,” or “beauty calibrator,” at first throws some grease on the smoking remains of your self-esteem by scrutinizing your face for ugliness you can’t even see. By 1932, inventor Max Factor had overhauled film cosmetics, replacing ruddy Vaseline and flour masks of the stage with his scientifically perfected flexible “greasepaint” cosmetics, pliable and resilient under studio lighting, constantly tweaked along with technological updates in clearer and more granular film. According to his biographraphy Max Factor: The Man Who Changed the Faces of the World, his concoctions were an asset to filmmakers like Charlie Chaplin and Cecil B. De Mille, his application rebooted careers with Hunter’s Bow lips for Joan Crawford and lighter skin for Rudolph Valentino, and exploded onto the commercial market when he and his son adapted “pan-cake” makeup for Technicolor. (Max Factor cosmetics still exists on the commercial market today).

The beauty micrometer thankfully flopped.

A blurb from a January 1935 issue of Modern Mechanix explains: “Flaws almost invisible to the ordinary eye become glaring distortions when thrown upon the screen in highly magnified images; but Factor’s ‘beauty micrometer’ reveals the defects.” The “defects” in Factor’s opinion were inconsistencies in what he considered the ideal facial ratio: eyes should be one eyeball-width apart, and nose length the same as the length of the forehead. Once flaws such as long noses and “weak” chins were detected within 1/100th of an inch, a cosmetician would use the info to paint over the problems.

The implications are disturbing.

Mimi Thi Nguyen, associate professor of gender and women’s studies and Asian American studies at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, and author of the book The Promise of Beauty, pointed out via email that the micrometer came at a time of peak interest in the pseudo-science of physiognomy–an assessment of moral character based on facial features and body type. “Long used to assign criminality, deviancy, and primitiveness to people of color, and the poor, physiognomy was deeply entwined with the rise of eugenics in the 1920s and ‘30s, which shaped U.S. cultures from law to beauty,” she wrote. “The association of beauty with symmetry, and symmetry with goodness, is thousands of years old in Western aesthetics, but the micrometer appears to promise ever more precision in one’s judgements in a period obsessed with minute degrees of ‘racial contamination.’”

“[W]hat Max found was that there is no such thing as the perfect face,” an assistant curator at the Beauty Museum (now the Hollywood Museum) told The San Francisco Examiner in 1991. “There are just perfect proportions.”

According to the Hollywood Museum, their model (currently on display in the Max Factor Building) is the only known surviving beauty micrometer.

The glamour bonnet (1941)

Have you ever noticed how great you look upon deboarding a long flight? Do you sometimes ask yourself how you can better mimic the fair beauty of a mountain climber? Did you know that reducing your air supply gives you a youthful glow? Based on one woman’s belief, that’s a hard “maybe,” according to an ad for the Glamour Bonnet, a scuba diver-esque helmet in which wearers would sit while oxygen levels were reduced. A March 1941 piece in Popular Science described the theory: “Some persons believe a mud pack is the answer to the search for beautiful complexion, others think massage will do the trick, but Mrs. D M Ackerman of Hollywood, Calif., has decided that reduced that reduced air pressure is a good treatment.

So she has devised a ‘glamour bonnet’ like a diver’s helmet with which the atmospheric pressure around the beauty seeker’s head can be lowered. The effect is similar to what a person feels who climbs a high mountain or flies high in a plane, and Mrs. Ackerman claims that the reduced pressure stimulates blood circulation and thus aids the complexion to attain its natural beauty. A window has been installed so the customers can read during treatments.” Apparently it didn’t go far, as it barely got a mention in print outside of this clip.

Dynatone (Late 1960s)

“You’ll think you look younger in just 3 days!” This definite possibility was promised by a 1968 newspaper ad for a luxury handheld facial toning device Dynatone. In the 50s and 60s, the prefix “dyna,” vaguely meaning “power” (“dynamic, dynamo, dynamite”), liberally affixed itself like exclamation points to innumerable garden variety items like “Dyna-Range,” a hearing aid attached to eyeglasses, “Dyna-flyte” indestructible golf balls, and “Dyna-Surge Tumble-Action” washing machines. There were Dyna stereos, Dyna basses, Dyna bikes, Dyna pool cues, Dyna-Kleen power vacs–evidently nothing could not be made better with more “dyna.” Like all of those things, the Dynatone leaned heavily on the copy and light on the science.

The Dynatone, which retailed for around $70 ($506 today), resembled an electric razor topped with two metal balls which delivered mild battery-generated electric shocks to the face, promising to tone the underlying muscles, thereby eradicating fine lines, wrinkles, and double-chin. “You see, true beauty is deeper than the skin,” Dynatone assures its prey. “It rests in those tiny underlying muscles that support your face and neck.”

“The exclusive new DYNATONE way electronically exercises hidden face and neck muscles and gently coaxes them back to youthful resiliency and tone,” it adds. “Used daily, DYNATONE easily and quickly firms up delicate facial muscles that cause double-chins, ‘crow’s feet’ and other facial contour problems.”

In 1970, the FDA seized 46 units from a Minneapolis department store for, among other reasons, the company’s spurious marketing claims, which a district judge found false and misleading. One doctor testified that rubbing the skin probably made wrinkles worse, and the court assertedthat continued use could cause nerve damage. In 1984, Dynatone was at the forefront of an FDA awareness-raising campaign about quackery.

The same general electric-workout theory applied to Dynatone’s offshoot the “Dynabelt,” one of the many iterations of the no-work-workout unisex waistband which burns calories for you while you watch TV. Perhaps. Today, you can legally strap into an Electric Muscle Stimulationsuit which delivers electric pulses to the muscles, making them bulk up more while you work out; while studies have shown that short-term use of electric stimulation on atrophied muscles can prevent the loss of muscle mass, it’s generally found that it does not preserve or increase strength.

The Epilady (1986)

The electric hair removal device Epilady made it into millions of bathtubs… and ultimately back to the store. The rotating metal coils uprooted hairs individually, leaving users with two weeks of silky smooth skin. It was also excruciating.

“Consumers got so caught up in the Epilady fad that many who shouldn’t have bought them—women who couldn’t tolerate the pain—got the gadgets anyway, only to return them later,” the Los Angeles Times wrote in September 1990. According to a New York Magazine feature, Joan Rivers is said to have compared the screams of a murder victim to the sound of an Epilady session. (The Epilady’s namesake “epilate” dates back to “épileurs,” 19th century French servants employed by hospitals to pluck the hair of patients with parasitic disease.) This 1992 commercialpromised that the new models were up to “30 percent more comfortable”–but by then, it was too late.

Epilady came from a kibbutz in Israel, was aggressively pushed onto the consumer market and burned out by its third year. Epilady mania had erupted almost immediately after its 1986 debut, generating over $340 million ($750 million now) in its first two years and copycat products around the world. Leggy models with Epiladys stormed TV commercial breaks in a $45 million-per-year advertising blitz. In February 1990, the trio leading the US distributor, the Krok sisters, entered the warm embrace of the New York Magazine’s style pages, which gushed: “What Nancy Reagan and Imelda Marcos are to buying, the Krok sisters are to selling—goddesses of the art.” Six months later, the company filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, and by 1991, Management Today compared the Kroks to Donald Trump: “‘80s entrepreneurial heroes” who became a “‘90s embarrassment.”

“Today, EPI’s [Epilady’s parent company’s] collapse is an example of the hazards of hype, over-optimism and, some creditors allege, of wild spending and financial fraud,” the Los Angeles Times ruled. According to the current US distributor, they’d overmanufactured for the previous Christmas and couldn’t handle the returns.

The Kroks’ distribution company folded, and soon after the Israeli manufacturer followed. But for diehard fans, Epilady love burns eternal; Isreali investors bought the intellectual and naming rights to Epilady in 1999, and a US distributor EpiladyUSA–who estimate the five percent of American women still epilate–claim they still gets calls from users with 25-year-old devices. The company has pivoted from the coils to rotating micro-tweezers which EpiladyUSA’s vice president Amir Abileah says is less painful (actually, Abileah specified that they don’t use the word “pain,” they use “discomfort,” and as a verb, “ouch,” as in: “any time you remove hair by the roots, it’s going to ‘ouch’”) and is allegedly enjoying steady growth largely thanks to online shopping.

Rejuvenique face mask (1995)

In just two and a half decades, the Rejuvenique Face Mask has already cemented its status as a fail for the ages, now a featured item in the Swedish-based Museum of Failure. In 1995, chiropractor George Springer unveiled his $395 (today $652) prototype to a gathering of spa owners in Florida; he always got the side-eye for this one. A January 26, 1995 articlein the Tampa Bay Times describes the intention as “aerobics for the face” with pulsing screws which massaged the muscles and delivered mild electric shocks (essentially Dynatone ‘95) to each of the twelve “facial zones”–a concept which informs you that your face is a dodecahedron (and newfound awareness that other products may have been neglecting zones this whole time). None of Rejuvenique’s claims were backed by scientific evidence, but by Springer’s bald faith.

“Springer acknowledges that he is selling a dream,” the Times writes. “‘The only difference is that it’s a dream come true,’ he says.”

Springer was sort of right, speaking for himself at least. In 1999, he struck a deal with Salton/Maxim, a forerunner in the shopping channel market, which enlisted Dynasty star Linda Evans as a paid sponsor and even placed the mask on shelves at Sears and Target. But the dream was fleeting. In 2000, the FDA issued a warning letter declaring the mask unsafe, stating that without FDA approval “marketing Rejuvenique is a violation of the law.”

A 2001 letter confirms that Rejuvenique was allowed to continue marketing its product. But around 2001, Linda Evans and the mask mystifyingly vanished from the ad spots; the FDA has no further records, Springer has retired from his Clearwater office, the Rejuvenique site is a dead link, Salton doesn’t list it for sale, and Amazon has only used models. At least one person, however, still uses it.

That person is Linda Evans.

Upon request, Evans’s management team confirmed that the review is authentic, that the masks were discontinued for reasons she doesn’t remember, but “she does use it and it works remarkably well for her.”

Smart hairbrush (2017)

Envision yourself as a living fountain of data, everything you do generating a constant stream of information to be siphoned into the vast irrigation system of targeted ads, and voilà: you have the Kérastase Hair Coach Powered by Withings. Developed with L’Oréal’s Research and Innovation Technology Incubator, the world’s first smart hairbrushcollects “data” on your hair status, such as dryness and frizziness, which then feeds into an app which analyzes the atmospheric conditions around the hair. Why? “By tracking the way a person brushes and factoring in aspects of daily life, the smart brush app provides valuable information including a hair quality score, data on the effectiveness of brushing habits, personalized tips and Kérastase product recommendations,” reads the press release.

The Verge panned it when it was unveiled at the trade show CES (Consumer Electronics Show). The product was never released. Two years later, you won’t find it on sale today. A representative from L’Oréal wrote over email that the company is “integrating insights” from consumer and professional feedback into future technologies. They did not respond to further request for comment.

The truth is necks waddle, chins double, eyes crease, collagen degrades, noses sag, and cells die. As dermatologist Robert Polisky told the Chicago Tribune about the Rejuvenique in 2000: “The skin really goes through a period of atrophy as we grow older. No one likes to hear that, but it does.”

It seems the vestigial pseudoscientific beauty gadget, too, is sliding into inevitable atrophy; things that strap on, plug in, are battery operated, or as-seen-on-TV emanate quackery after one too many lawsuits, recalls, missing thingies, reality shows about purging the detritus from shopping binges of the past. Clunky gadgets may be a passing phenomenon, but in the place of magic bullets, America has found magic itself; with a dash of belief and a heap of disposable income, we bathe in vitamins and serums, bask in the light of Himalayan salt lamps, breeze through the mist of good-vibes chakra spray, receive the healing photons of lasers, lie beneath cryolipolysis wands which melt our fat cells, revitalize our faces with emollient of mud. Mud–mud!–can be a wild success. Which means that potentially, even mud can be a great fail.

[“source=gizmodo”]