The ashes filled a black plastic box about the size of a toaster. It weighed three and a half pounds. I put it in a canvas tote bag and packed it in my suitcase this past July for the transpacific flight to Manila. From there I would travel by car to a rural village. When I arrived, I would hand over all that was left of the woman who had spent 56 years as a slave in my family’s household.

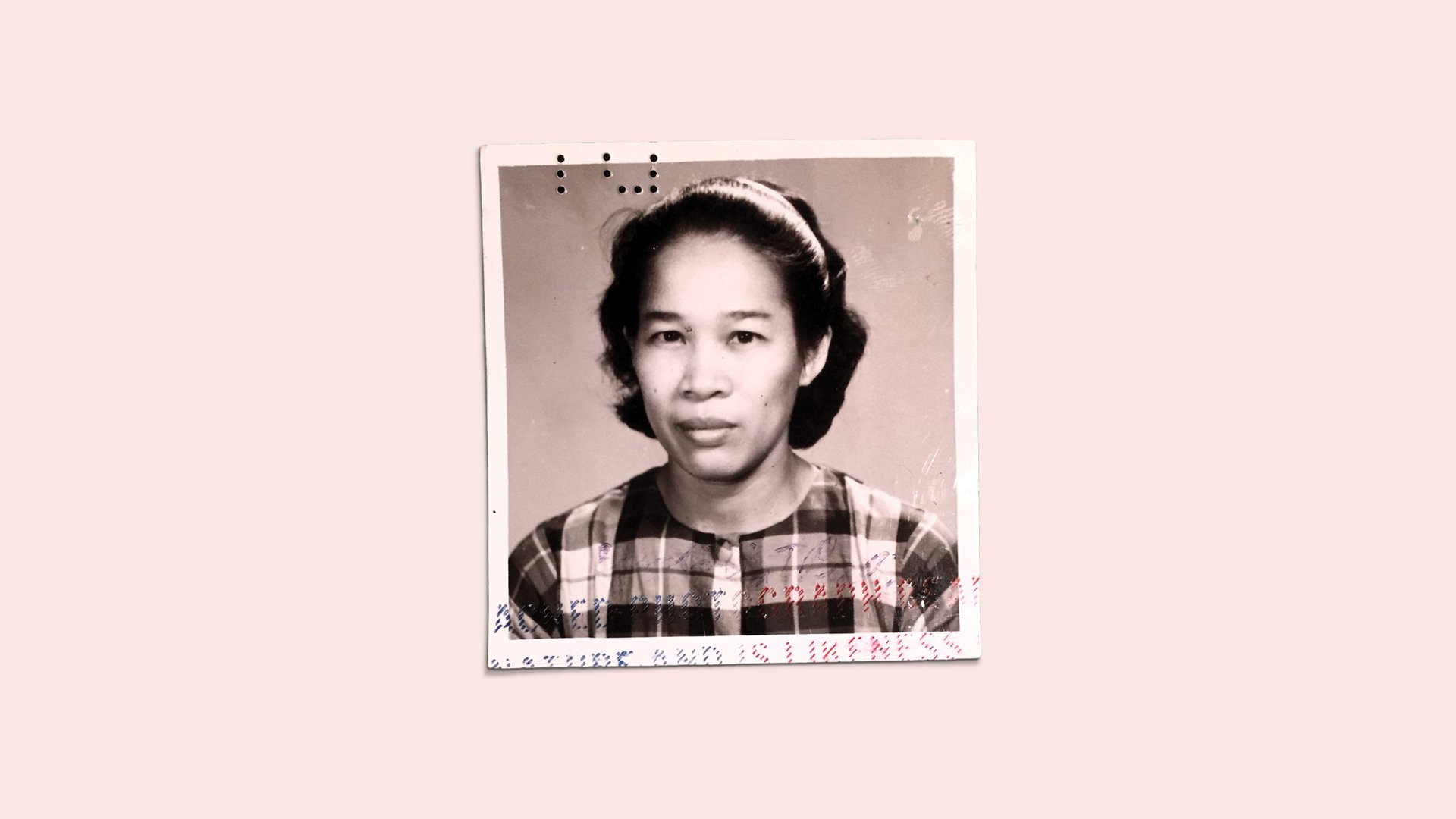

Her name was Eudocia Tomas Pulido. We called her Lola. She was 4 foot 11, with mocha-brown skin and almond eyes that I can still see looking into mine—my first memory. She was 18 years old when my grandfather gave her to my mother as a gift, and when my family moved to the United States, we brought her with us. No other word but slave encompassed the life she lived. Her days began before everyone else woke and ended after we went to bed. She prepared three meals a day, cleaned the house, waited on my parents, and took care of my four siblings and me. My parents never paid her, and they scolded her constantly. She wasn’t kept in leg irons, but she might as well have been. So many nights, on my way to the bathroom, I’d spot her sleeping in a corner, slumped against a mound of laundry, her fingers clutching a garment she was in the middle of folding.

To our American neighbors, we were model immigrants, a poster family. They told us so. My father had a law degree, my mother was on her way to becoming a doctor, and my siblings and I got good grades and always said “please” and “thank you.” We never talked about Lola. Our secret went to the core of who we were and, at least for us kids, who we wanted to be.

After my mother died of leukemia, in 1999, Lola came to live with me in a small town north of Seattle. I had a family, a career, a house in the suburbs—the American dream. And then I had a slave.

At baggage claim in Manila, I unzipped my suitcase to make sure Lola’s ashes were still there. Outside, I inhaled the familiar smell: a thick blend of exhaust and waste, of ocean and sweet fruit and sweat.

Early the next morning I found a driver, an affable middle-aged man who went by the nickname “Doods,” and we hit the road in his truck, weaving through traffic. The scene always stunned me. The sheer number of cars and motorcycles and jeepneys. The people weaving between them and moving on the sidewalks in great brown rivers. The street vendors in bare feet trotting alongside cars, hawking cigarettes and cough drops and sacks of boiled peanuts. The child beggars pressing their faces against the windows.

Lieutenant Tom had as many as three families of utusansliving on his property. In the spring of 1943, with the islands under Japanese occupation, he brought home a girl from a village down the road. She was a cousin from a marginal side of the family, rice farmers. The lieutenant was shrewd—he saw that this girl was penniless, unschooled, and likely to be malleable. Her parents wanted her to marry a pig farmer twice her age, and she was desperately unhappy but had nowhere to go. Tom approached her with an offer: She could have food and shelter if she would commit to taking care of his daughter, who had just turned 12.

“She is my gift to you,” Lieutenant Tom told my mother.

“I don’t want her,” my mother said, knowing she had no choice.

Lieutenant Tom went off to fight the Japanese, leaving Mom behind with Lola in his creaky house in the provinces. Lola fed, groomed, and dressed my mother. When they walked to the market, Lola held an umbrella to shield her from the sun. At night, when Lola’s other tasks were done—feeding the dogs, sweeping the floors, folding the laundry that she had washed by hand in the Camiling River—she sat at the edge of my mother’s bed and fanned her to sleep.

One day during the war Lieutenant Tom came home and caught my mother in a lie—something to do with a boy she wasn’t supposed to talk to. Tom, furious, ordered her to “stand at the table.” Mom cowered with Lola in a corner. Then, in a quivering voice, she told her father that Lola would take her punishment. Lola looked at Mom pleadingly, then without a word walked to the dining table and held on to the edge. Tom raised the belt and delivered 12 lashes, punctuating each one with a word. You. Do. Not. Lie. To. Me. You. Do. Not. Lie. To. Me. Lola made no sound.

Seven years later, in 1950, Mom married my father and moved to Manila, bringing Lola along. Lieutenant Tom had long been haunted by demons, and in 1951 he silenced them with a .32‑caliber slug to his temple. Mom almost never talked about it. She had his temperament—moody, imperial, secretly fragile—and she took his lessons to heart, among them the proper way to be a provincial matrona: You must embrace your role as the giver of commands. You must keep those beneath you in their place at all times, for their own good and the good of the household. They might cry and complain, but their souls will thank you. They will love you for helping them be what God intended.

My brother Arthur was born in 1951. I came next, followed by three more siblings in rapid succession. My parents expected Lola to be as devoted to us kids as she was to them. While she looked after us, my parents went to school and earned advanced degrees, joining the ranks of so many others with fancy diplomas but no jobs. Then the big break: Dad was offered a job in Foreign Affairs as a commercial analyst. The salary would be meager, but the position was in America—a place he and Mom had grown up dreaming of, where everything they hoped for could come true.

Dad was allowed to bring his family and one domestic. Figuring they would both have to work, my parents needed Lola to care for the kids and the house. My mother informed Lola, and to her great irritation, Lola didn’t immediately acquiesce. Years later Lola told me she was terrified. “It was too far,” she said. “Maybe your Mom and Dad won’t let me go home.”

In the end what convinced Lola was my father’s promise that things would be different in America. He told her that as soon as he and Mom got on their feet, they’d give her an “allowance.” Lola could send money to her parents, to all her relations in the village. Her parents lived in a hut with a dirt floor. Lola could build them a concrete house, could change their lives forever. Imagine.

We landed in Los Angeles on May 12, 1964, all our belongings in cardboard boxes tied with rope. Lola had been with my mother for 21 years by then. In many ways she was more of a parent to me than either my mother or my father. Hers was the first face I saw in the morning and the last one I saw at night. As a baby, I uttered Lola’s name (which I first pronounced “Oh-ah”) long before I learned to say “Mom” or “Dad.” As a toddler, I refused to go to sleep unless Lola was holding me, or at least nearby.

I was 4 years old when we arrived in the U.S.—too young to question Lola’s place in our family. But as my siblings and I grew up on this other shore, we came to see the world differently. The leap across the ocean brought about a leap in consciousness that Mom and Dad couldn’t, or wouldn’t, make.

Lola never got that allowance. She asked my parents about it in a roundabout way a couple of years into our life in America. Her mother had fallen ill (with what I would later learn was dysentery), and her family couldn’t afford the medicine she needed. “Pwede ba?” she said to my parents. Is it possible? Mom let out a sigh. “How could you even ask?,” Dad responded in Tagalog. “You see how hard up we are. Don’t you have any shame?”

My parents had borrowed money for the move to the U.S., and then borrowed more in order to stay. My father was transferred from the consulate general in L.A. to the Philippine consulate in Seattle. He was paid $5,600 a year. He took a second job cleaning trailers, and a third as a debt collector. Mom got work as a technician in a couple of medical labs. We barely saw them, and when we did they were often exhausted and snappish.

Mom would come home and upbraid Lola for not cleaning the house well enough or for forgetting to bring in the mail. “Didn’t I tell you I want the letters here when I come home?” she would say in Tagalog, her voice venomous. “It’s not hard naman! An idiot could remember.” Then my father would arrive and take his turn. When Dad raised his voice, everyone in the house shrank. Sometimes my parents would team up until Lola broke down crying, almost as though that was their goal.

It confused me: My parents were good to my siblings and me, and we loved them. But they’d be affectionate to us kids one moment and vile to Lola the next. I was 11 or 12 when I began to see Lola’s situation clearly. By then Arthur, eight years my senior, had been seething for a long time. He was the one who introduced the word slave into my understanding of what Lola was. Before he said it I’d thought of her as just an unfortunate member of the household. I hated when my parents yelled at her, but it hadn’t occurred to me that they—and the whole arrangement—could be immoral.

“Do you know anybody treated the way she’s treated?,” Arthur said. “Who lives the way she lives?” He summed up Lola’s reality: Wasn’t paid. Toiled every day. Was tongue-lashed for sitting too long or falling asleep too early. Was struck for talking back. Wore hand-me-downs. Ate scraps and leftovers by herself in the kitchen. Rarely left the house. Had no friends or hobbies outside the family. Had no private quarters. (Her designated place to sleep in each house we lived in was always whatever was left—a couch or storage area or corner in my sisters’ bedroom. She often slept among piles of laundry.)

We couldn’t identify a parallel anywhere except in slave characters on TV and in the movies. I remember watching a Western called The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. John Wayne plays Tom Doniphon, a gunslinging rancher who barks orders at his servant, Pompey, whom he calls his “boy.” Pick him up, Pompey. Pompey, go find the doctor. Get on back to work, Pompey! Docile and obedient, Pompey calls his master “Mistah Tom.” They have a complex relationship. Tom forbids Pompey from attending school but opens the way for Pompey to drink in a whites-only saloon. Near the end, Pompey saves his master from a fire. It’s clear Pompey both fears and loves Tom, and he mourns when Tom dies. All of this is peripheral to the main story of Tom’s showdown with bad guy Liberty Valance, but I couldn’t take my eyes off Pompey. I remember thinking: Lola is Pompey, Pompey is Lola.

[“Source-theatlantic”]