Jacob didn’t always know how to answer him in the moment. She remembered the confusing conversations about race and identity that she’d had as a child herself, growing up in one of the few South Asian families in New Mexico. But having those conversations with her son in the years leading up to Donald Trump’s presidency made her realize that there weren’t any easy answers to the question of what it means to grow up as a person of color in the United States.

Even though she’s a writer by trade, Jacob couldn’t find the words to describe what she was feeling. She often felt paralyzed thinking about the hurtful comments she might receive online if she did write openly about those tricky conversations. But she still felt the urge to record them somehow, and that led her to producing a memoir in the form of a graphic novel. The book, Good Talk, spans from her childhood in New Mexico to her more recent arguments with in-laws who wanted to vote for Trump and who she felt weren’t listening to her concerns about his racist rhetoric on the campaign trail.

Good Talk is a series of honest but not always conclusive conversations with various family members at different stages in her life: as an insecure high schooler, an aspiring writer in New York, and a mother trying to figure things out as she goes. I spoke with Jacob about the process of writing and illustrating the memoir, her family’s reaction to it, and how stereotypes about interracial families compare with reality. This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Amal Ahmed: In this memoir, you showcase a lot of really intimate moments between you and your family members. What made you want to tell those stories?

Mira Jacob: I never set out to write a memoir. I wouldn’t have said that was my forte, because of the level of vulnerability and transparency that it requires. My family is very private. Having said that, I think that the years leading up to Trump’s election, which are recounted in the book— the moments in which my son was forming his identity as a young brown boy— were made pretty harrowing by the rise of Trump and also my in-laws’ support of Trump. It was really confusing for him. It was really confusing for me, frankly. I didn’t know how to answer his questions and anxieties, which is always something you want to do as a parent. And I couldn’t answer my own anxieties, I realized.

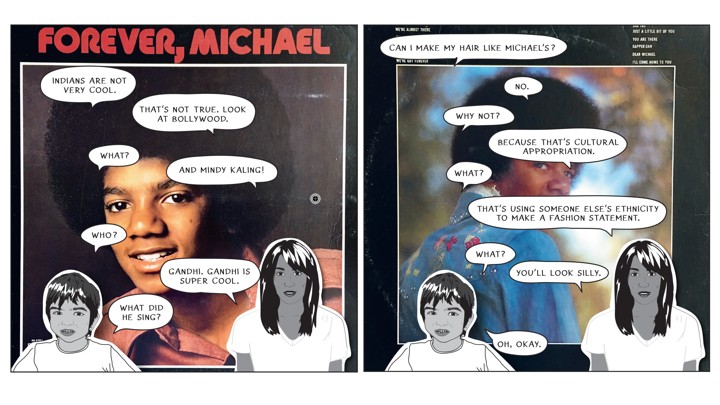

One day I was sitting around and I was having these conversations with my son about Michael Jackson that were so crazy—they were so funny, and deeply sad. I realized I couldn’t explain that to anyone— there was no sentence that was going to make sense of it. So I just wrote down the conversation instead. I drew us on printer paper, and I cut us out and put us on top of Michael Jackson albums. I wrote the conversations on bubbles, and took pictures of it standing up on our dining-room table and sent them to a friend at BuzzFeed, Saeed Jones [who published them]. That piece went really, really viral. I knew I had the book in me already, but that was the catalyst.

Ahmed: Why did you decide to tell this story in a graphic novel, specifically with these illustrations of conversations?

Jacob: As a creative person, I do my best when I’m learning. I didn’t know how to draw very well when I started. And I didn’t know how to draw on a screen, which is a whole other thing. So I had to figure out these different softwares and how to draw with a stylus and how to put things into InDesign.

Something that always jars people is that the expressions on the characters’ faces never change. They always stay the same: a neutral and flat expression. My first editor said, “It’s really jarring when these hard conversations are happening and the faces stay frozen. Do you want to put an expression on them?” And I said, “Absolutely not.” The discomfort it unleashes when you’re reading it was the same discomfort I had walking around America watching everything sort of slide into the shitter in 2015. So it felt really freeing for me not to perform the racial pain that Americans, I think, hunger for and then love to dismiss.

Read: The art of navigating a family political discussion, peacefully

Ahmed: In the first few chapters of your book, you have these old photos of your family—your parents and your brother and you when you were little. Why did you want to include those?

Jacob: I really love these old photos of my family in New Mexico. I love all my aunties in saris going on hikes up the Sandia Mountains. I love the dissonance of that—you don’t see that anywhere. When we talk about Indians, we’re like, We need diversity now! Where are those 2019 Indians? Well, where are the ones from the ’60s and ’70s? I went through old family albums and pulled out all the ones I used to stare at when I was little. Like the one of my mother arriving in my parents’ first house in Albuquerque. She’s a little blip in a sari in the doorway, and the desert was so huge and vast and empty. It was really fun to do that, to show something that I was sure other people knew about their families too, but had never seen like this in a book.

Ahmed: In the acknowledgments, you write that your mom and brother were really supportive of this book, but when they read it, they would say things like I don’t remember that at all. Did you give them a heads-up about the conversations that went into the book, or ask how they remembered those moments?

Jacob: I didn’t ask them how they remembered moments. I think we all have those conversations that just live in our brains forever, because they have informed some part of us so deeply. It almost doesn’t matter how the other person remembers it, because you have taken it in a specific way. So given that conversations are complicated and no one agrees on what was said, I gave the book to my family and in-laws before I published it. I said, “This is what’s in there and let’s talk.” No one said, “You can’t do this.” I imagine that my mother is much more complicated than she appears on the panels in the book, and so are my in-laws and my husband and my child— and so am I. This is a portion of us, and it’s never going to be all of us. And I think we all know that.

Ahmed: On that note, I think you do a really good job of telling stories about your parents and growing up in New Mexico that don’t become caricatures of that experience. But there are a lot of themes that are going to be familiar to your South Asian readers particularly. How did you strike the balance of telling this specific story and drawing out more universal themes?

Jacob: I wasn’t trying for the universal themes at all, to be up front. But I do think that many South Asian families experience something similar, because we are always treated as a new thing. My parents have been here since the late ’60s. There are Indians who have been in this country since the ’20s. We are always treated like brand-new interlopers who are lucky to be here. My parents moved to a place where there weren’t a lot of other South Asians at all. We had the constant battle of explaining who we were. I don’t think I knew there was another way to live, but then I came east for college and I remember meeting Indians from New Jersey. They were like, Wait, you didn’t have 200 people you were hanging out with and going to functions with? And I was like, I don’t know what you’re talking about. There were seven of us.

Ahmed: There’s a scene in the book where you encounter an editor like this at a radio station. Can you describe that for me, and tell me why you wanted to include that in your memoir?

Jacob: I’d written a novel, my first book, The Sleepwalker’s Guide to Dancing. A radio station had asked me to read a section on the air, and the editor said, “You know, this is great, but the unusual names are going to be really hard for our listeners. Do you need to have three characters with unusual names?” So I was like, What do I do with that? I turned to my husband and asked, “Am I supposed to change the names?” And he said, “Good lord, no, you have to protect your work against bad ideas.”

I wrote back to the editor and I said, Let’s keep the names of the characters in this book that is already published. I said later to my best friend, it’s like every door I go through, this guy is on the other side patting himself on the back for letting me through while demanding I scrub myself down before I enter. It’s so humiliating to always be in that position.

Ahmed: While this is going on with the editor, you have an argument with your husband about the right approach to take. The fight stems from something professional but spills into your personal life. Why was it important to you to show that side of your marriage?

Jacob: I think that America has a kind of fantasy about what an interracial relationship is like—people who understand each other from the get-go; they are the future; they will save humanity and all babies will be beige—I mean, there’s a real deep fantasy about this.

But we know that can’t be true. We have too many things we misunderstand about each other. So then people assume that people who are together from different races secretly hate themselves and their culture. There is a distrust of interracial relationships, too.

What I wanted to write about was not the kumbaya fantasy or the gross assumptions, but the actual reality. It’s all of these things: We have moments of tremendous love, and we have tremendous dissonance. We have moments when we get each other, and moments when we’ve really failed each other. That’s what that love looks like. It’s complicated and it is real. The minute you’re not allowed to investigate your own interiority and complexity, you’ve lost. I wanted to stop losing.

Ahmed: What do you mean by “You’ve lost”?

Jacob: What I kept telling myself to make myself brave when I was like, Why are you writing this book? is that America is a dumpster fire of political opinions, and it is hard to be vulnerable about anything. Everyone wants to be on the right side of everything. Why write a book in which you are clearly making so many mistakes and you are not solely on the right side? I wanted to write it because I felt that we were becoming a monolith in America, as people of color. The minute you’re not allowed to explore your own complexity and interrogate yourself, you’ve had to become someone else’s version of you. And I don’t want to do that—try to make myself bulletproof and only present the best part of myself. You lose so much if you can only ever be the best parts of yourself. It’s not a human way to move through this world.

[“source=theatlantic”]