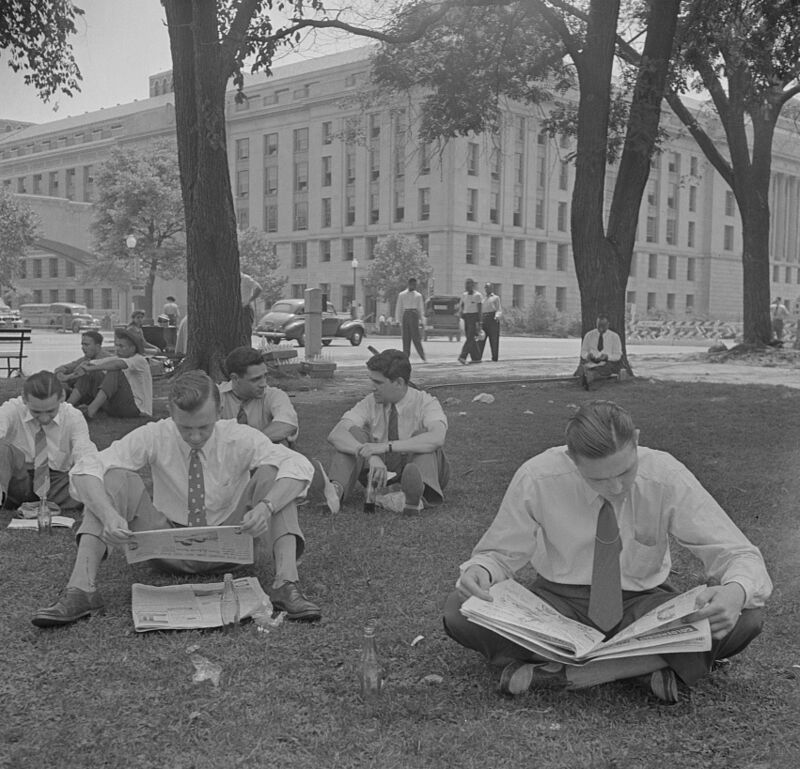

Think of all the paper they could be shuffling.

Photographer: Marjory Collins/Library of Congress

In his new book “The Complacent Class,” my Bloomberg View colleague Tyler Cowen mentions that more Americans may be slacking off at work. He offers this as one more measure of the comfortable malaise into which American culture has settled. But it also occurs to me that if leisure is replacing effort at work, it means that the country may be getting more productive more quickly than economists realize.

Productivity is a measure of how much output the economy can get for a given amount of inputs. Total factor productivity measures output as a function of labor and capital both, while labor productivity takes only workers’ time and effort into account. Both have been slowing in developed countries in the past decade. Here’s a picture of U.S. labor productivity:

The recent slowdown is worrying, because it means the economy isn’t producing much more with each hour of work than it was a decade ago. In the short run, productivity can be hurt by things like recessions, but in the long run it’s a pretty good indicator of the economy’s overall ability to produce value. A productivity slowdown can be the result of fewer new technologies, more onerous government regulations and taxes, a less-skilled workforce, worse management practices or increased trade barriers.

But if the inputs are being measured incorrectly, then the productivity numbers aren’t telling us an accurate story. Labor productivity is output divided by hours of work. If the number of work hours has been overstated more and more as time goes on, it means productivity has been increasing faster than the official numbers indicate.

For many workers, the pressures of a modern job are intense. Doctors spend all their hours in hospitals, engineers scramble to meet deadlines, lawyers burn the midnight oil working to make partner. But for anyone who works in a modern office, there are distractions available that just didn’t exist 25 years ago. You can talk to your friends and coworkers on Slack and Facebook Messenger and Snapchat. You can browse Twitter, check Reddit threads, or read excellent articles on Bloomberg View. You can watch video games on YouTube or Twitch. Internet and mobile technologies have made slacking off easier than ever.

Is technology causing people to fritter away time at work? It’s hard to measure long-term trends, since data on this question hasn’t been collected for very long, and is confounded by events like the Great Recession, which probably caused people to work harder for fear of losing their jobs.

But the raw numbers are substantial. The American Time Use Survey does ask workers about time at work spent not working, and the amount of time is significant — maybe 50 minutes a day for those who don’t claim to work every minute. A 2014 Salary.com survey put the numbers even higher. Here were the percentages:

Goof-Off Nation

Percent of respondents reporting how much time they wasted at work.

Source: Salary.com

The average working American spends about 34.4 hours on the job. If we assume that’s five days a week, it means that one hour of slacking per day means that true work hours are really only 85.5 percent of the official number. Labor productivity growth averaged about 0.3 percent in 2016. But if the internet increased wasted work time by just 2 percent that year, it would mean that labor productivity growth was actually about 2.3 percent that year — almost eight times faster than the recorded figure! That number would put recent productivity growth close to the levels of the 1980s and 1990s.

When output goes up while work effort falls, it means more is being done with less. If I can complete a task in two hours that used to take four, and spend the extra two hours surfing Twitter, it means that technology, management or some other aspect of the economy has gotten twice as good.

This could be part of the puzzle of missing productivity growth from information technology. In 1987, economist Robert Solow quipped that “You can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics.” Three decades later, many economists believe that the IT revolution lifted productivity only for a brief time in the 1990s and early 2000s. Economists scratch their heads when they ask why all the fantastic new tools Silicon Valley rolls out every year don’t seem to make the economy more efficient. But if IT is raising work productivity while simultaneously causing people to take more hidden leisure, the mystery is solved.

This might seem paradoxical. On-the-job loafing lowers economic output. But it also causes mismeasuring work input, meaning that real productivity is understated. Even if slacking off is a bad thing, it could be good news for technological progress.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

[“Source-bloomberg”]