Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Ltd. has cut the number of workers on its turbocharger production lines west of Tokyo by more than 80 percent, as Japanese manufacturers from carmakers to electronics producers push further into automation.

Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Ltd. has cut the number of workers on its turbocharger production lines west of Tokyo by more than 80 percent, as Japanese manufacturers from carmakers to electronics producers push further into automation.

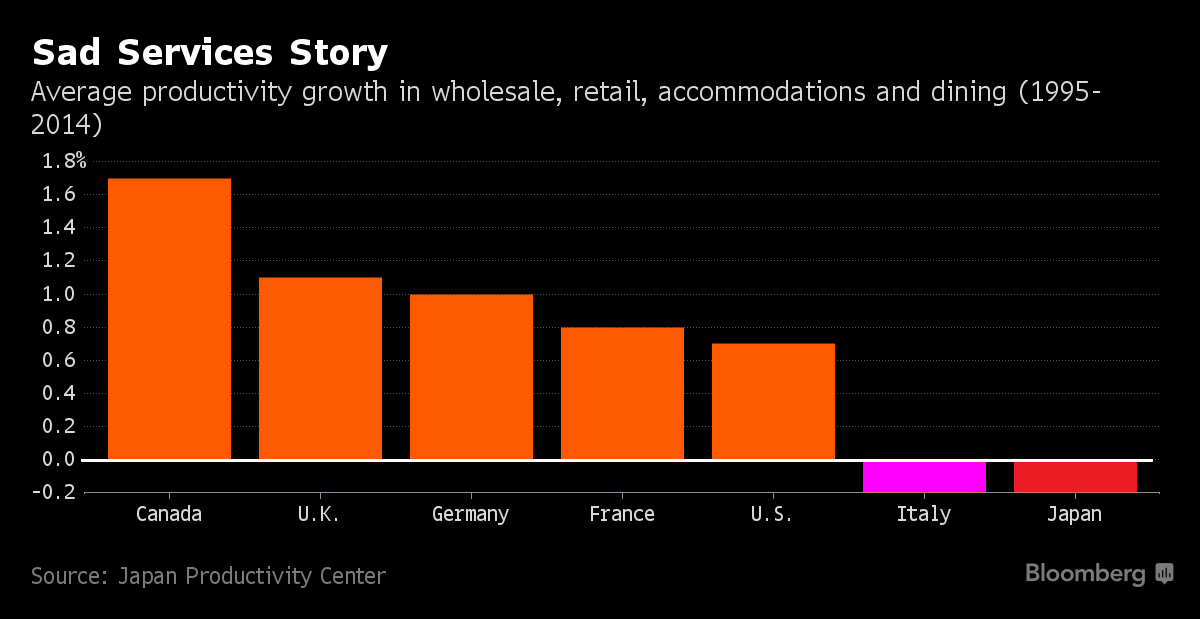

Such advances explain why Japan’s factory productivity growth ranked highest among Group of Seven nations over the two decades to 2014. Yet the nation’s overall productivity ranks worst in the G7, dragged down by a lack of progress in the services sector, where the white-collar work culture demands long hours rather than efficiency.

Higher productivity is critical to sustaining economic growth and living standards as Japan’s population shrinks. One forecast predicts the current labor force of about 77 million could collapse by more than 40 percent by 2065. With the services sector now accounting for more than two-thirds of the economy, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has targeted a doubling of productivity growth in this area to 2 percent by 2020.

Unfortunately, most of gains are still limited to companies like Mitsubishi Heavy, which cut its 20-person turbocharger lines in Sagamihara to three people as the lathes were automated to produce parts.

The workers not needed on the line were switched to different jobs, said Joseph Hood, a Tokyo-based spokesman. The company plans to expand production to 12 million units by 2020 to meet growing demand, from 9 million last year, he said.

Japan isn’t alone with its productivity woes. In the U.S., poor productivity has has been a factor behind the reluctance of employers to fatten pay checks. The problem is more dire for Japan right now though because the drag it’s having on wages is undermining the central bank’s efforts to stoke much-needed inflation.

“In Japan, I think manufacturers are much more sensitive about productivity per hour than in the U.S. and Europe,” said Koichiro Imano, a former professor of economics at Gakushuin University in Tokyo. “They are very strict and so productivity in factories is very high. But it’s completely different for white-collar workers.”

In the offices ruled by Japan’s “salarymen,” it’s putting in long hours that still counts with many bosses.

Men in Japan work some of the longest hours in the world, according the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, with the average male working 8.9 hours a day, the highest of 26 countries surveyed after Mexico. That compares with 7.9 hours in the U.S. and 7.3 hours in the U.K., according to the OECD.

Domestically protected industries, which face limited competition from overseas, such as retailing and farming are also proving barriers to improved productivity. Services sector productivity in Japan was about half that of the U.S. from 2010 to 2012, according to data from the Japan Productivity Center.

“Some Japanese companies keep unprofitable businesses alive to maintain employment,” said Yasuhiro Kiuchi, the senior principal researcher at the Japan Productivity Center in Tokyo. “It’s common to keep businesses going if they’re not making big losses.”

One way Abe is aiming to boost productivity is by targeting a 20-fold increase in the market for service robots by 2020, and a doubling of the market for manufacturing robotics to the same amount by that time. Examples of service robots include bionic suits that help health care workers lift patients and androids that greet guests at hotels.

The nation’s flourishing convenience stores have bucked the trend in terms of efficiency and innovation. The owner of the 7-Eleven chain made its largest-ever purchase this month to expand its network in the U.S., where the original namesake brand went bankrupt and was bought by the Japanese arm. The company has honed its distribution system and created a system that adapts quickly to changing customer preferences.

“Wholesale and retail have been pointed to as one low-productivity industry, but as you can see from convenience stores there is nothing uncompetitive about them,” said Takuji Okubo, Tokyo-based chief economist at Japan Macro Advisors. “Convenience stores are relatively new and I think there has been less regulation and less impact from national associations and so they didn’t seek protection.”

[Source:-bloomberg]